Surveillance and Technology Session at Janta Parliament

Rethink Aadhaar and Article 21 Trust anchored a Session on Technology and Surveillance at the Janta Parliament on 18 August 2020.

At the sixth session of the Janta Parliament, the House resolved to urge the government to frame a people-centric digital rights law upholding “people’s right to personhood, dignity, equality, privacy, and self-determination”.

Members of the Peoples’ House resolved to urge the government to curtail unlawful and unconstitutional mass surveillance, and to bring all surveillance agencies under strict parliamentary and judicial scrutiny. Expressing concern on the gaping digital divide, the House urged the government to develop and promote people-friendly technological tools, and ensure that access to the Internet and other communication technologies is ensured for everyone in an equitable manner.

During the session, the session’s speakers, who represented diverse backgrounds and perspectives, critically appraised the use of technology in governance, justice, and welfare as well as the interaction of various communities with technology. The session was formally opened and presided over by Rupali Samuel, Advocate, Supreme Court of India, whose introductory remarks highlighted the “mass ostracization and harassment” faced by individuals who had their personal information regarding health status and travel history released in the public domain. She brought into sharp focus the legitimate demand of “trust” between people and the government.

Pushback on data commodification and invasion of privacy

The session opened with a keynote address delivered by Usha Ramanathan, legal researcher on law and poverty, who drew parallels between the exploitation of natural resources and the collection of data. She asserted that the understanding between state and corporate entities to promote use of certain data extractive business practices, with minimum regulatory oversight, needs to be critically examined, especially during times of crisis when people can be coerced to part with their data. She concluded by saying that the idea of transparency has been turned on its head where people are expected to reveal everything about themselves even as the government becomes more opaque with carrying out mass surveillance activities.

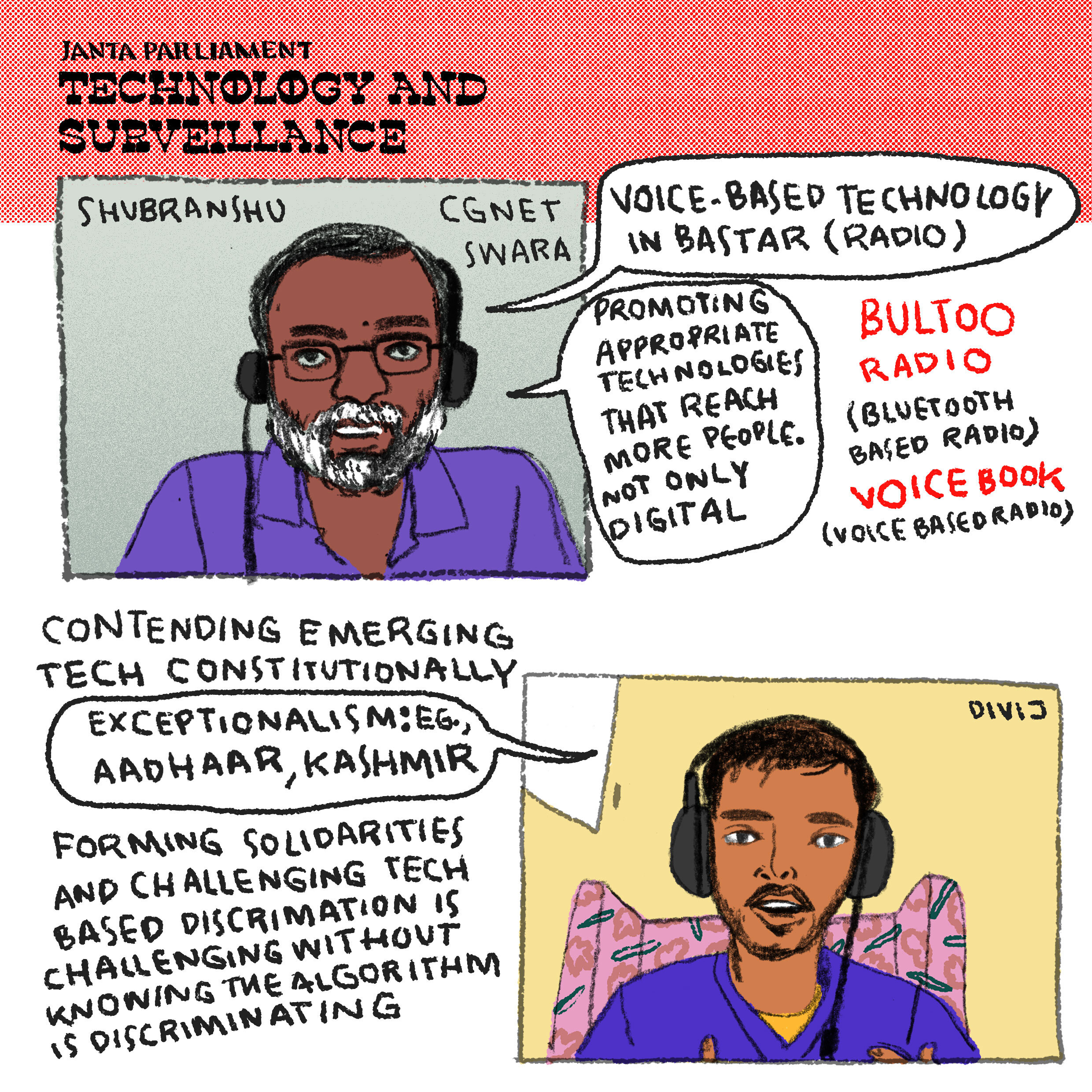

Astha Kapoor of the Aapti Institute highlighted the legitimate demands of platform workers who provide an essential public service during the pandemic but have no control or bargaining power - either individual or collective - over the data gathered about them. Asserting the need to understand data in its contextual setting and to resist from reducing humans to data points, Tripti Jain, of the Internet Democracy Project, made the case for data protection to go beyond digital rights to ensure bodily autonomy. Cautioning against furthering a regime of exceptionalism regarding technology and data collection practices in order to fuel the information economy, independent researcher Divij Joshi argued for the need to formulate “‘coordinated responses to algorithmic systems that create or use proxy information to discriminate against us in new and old ways”. Rahul Sharma from The Perspective highlighted the growing trend of referring to data as ‘oil’, ‘gold’, ‘uranium’, etc. and argued that the focus of data-related regimes needs to be brought back from economic growth to individual rights and decision-making autonomy.

Critical appraisal of access to and through technology

Navmee, a volunteer with the Stranded Workers Action Network, provided evidence through her work to show how migrant workers found it difficult to access government welfare schemes which were made available through website or app registrations, making owning a smartphone or otherwise having access to the Internet a precondition to avail emergency relief. An example of a woman living in a remote corner of northeastern India was cited by The Bachao Project’s Chinmayi SK to highlight how poor Internet access and inadequate communication infrastructure create barriers for people at a time when services ranging from education to banking are being moved online. Chinmayi also expressed concern over the restrictions on Internet and communications services experienced by the people of Jammu and Kashmir in the past year, stating that prolonged Internet deprivation had an impact on not just education and business opportunities but also on psychological well-being. Siddharth deSouza, Founder of Justice Adda, highlighted access concerns for those seeking justice as courts across India physically closed down and went virtual. He argued that virtual court management needs to be made people-centric and reviewed and redesigned taking into consideration concerns of all stakeholders especially litigants. Making a strong case for reconsidering regulations around use of a wider range of possibly more accessible forms of communication mediums such as Radio and BlueTooth, Shubhranshu Choudhary of CGNet Swara spoke of how, in the lesser developed parts of India, people rely on voice-based and other technologies which work even in areas without mobile or Internet connectivity.

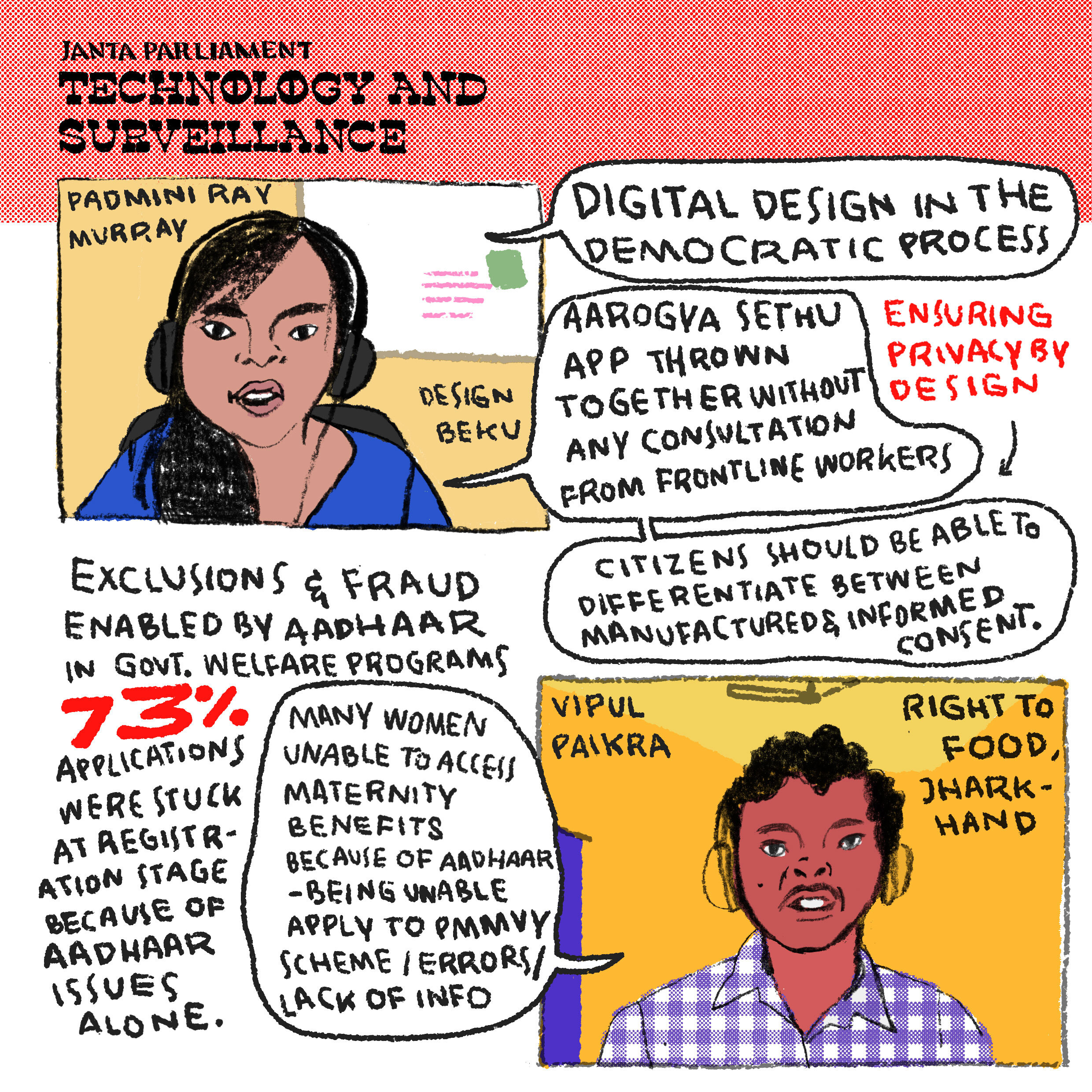

Citing the example of how the Aarogya Setu app was designed without seeking inputs from the ASHA workers who were at the forefront of the efforts to track and contain the spread of Covid-19, Design Beku founder Padmini Ray Murray argued for greater scrutiny of the impact of digital design on service delivery. Osama Manzar of the Digital Empowerment Foundation concluded the session’s arguments expressing his concerns over inequitable access by arguing that the private sector’s involvement for the most part in providing Internet access infrastructure has meant that people are treated solely as consumers rather than citizens, with the government bearing no responsibility or accountability. He further argued that, by adopting an interrogatory approach to citizens, the government seems to be interested only in extracting accountability from the people who are always under doubt.

Aadhaar’s Continuing Strangehold

Highlighting Aadhaar’s stranglehold of welfare programs Sameet Panda, with the Right to Food Campaign, Odisha, elaborated how despite evidence of denial of ration to people due to non-seeding or incorrect seeding of Aadhaar numbers, the Odisha government recently mandated Aadhaar linking for availing pensions, which will mar an otherwise well run welfare program. Arguing that already weak public health delivery systems of the country were further weakened by pushing for mandatory Aadhaar linkages, Deepika Joshi of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, criticized the fact that fetters to accessing health services during the pandemic were not removed. She provided the example of making Aadhaar mandatory to avail COVID-19 testing and drugs in Rajasthan and Maharashtra which raises issues around access and privacy for sensitive health data. Vipul Paikra, Right to Food Campaign, Jharkhand, shared stories from the ground in Jharkhand, concluding that the Aadhaar project which has been peddled to people as a ‘panacea’ has led to women being deprived of maternity benefits under the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and has enabled scams leading to siphoning off of funds meant for Pre-metric Scholarships.

Tackling Rampant Surveillance

Expressing caution around the rampant surveillance, and asserting that technology is political, Sweta Dash, an independent researcher & journalist, highlighted that not just bodies, but their actions, speeches and dissent are subject to surveillance and vulnerable to persecution. Kanksshi Agarwal, Centre for Policy Research, highlighted serious concerns with unregulated use of facial recognition technologies in law enforcement or in election related activities as used in a recently held municipal elections in Telangana with grave potential of violations of rights.

Arguing that Section 35 of the Personal Data Protection Bill granting powers to the Central Government to exempt any government agencies from certain provisions of Bill helps perpetuate unregulated surveillance practices, Anita Gurumurthy (co-Executive Director, IT for Change), called this “undermining of institutions a process of de-democratization”. While proposing a resolution for enacting a framework law on digital rights, she further argued that we need to move towards “an indivisible and integrated approach to digital rights” or what can be termed as “digital constitutionalism”. She also pointed out the need to recognise the cornering of the “intelligence premium,” to understand the social crisis we’re witnessing of how economic production is organised, due to Big Data and AI. She ended her intervention calling on civil society to engage with the idea of data as a resource, and that in the fight against neoliberal capital, and jingoism and state impunity, ensuring that there isn’t a denial of the idea that value inheres in data – but a recognition of its multivalence and that this value can be private, public or social. A crucial engagement is creating the boundaries to nurture the social, preserve the public and limit the private.

In the context of unregulated use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement agencies against women protestors, originally meant to be used for tracking missing children, Anusha Ravishankar of NETRI Foundation called for greater regulation on use and commercialization of such technologies. Arguing that the conceptualization of Aadhaar was not from a welfare perspective but from the capitalist idea of creating an information economy, Srinivas Kodali, an independent researcher, cautioned against the potential of Aadhaar infrastructure creating a 360 o degree profiling and surveillance mechanism by being linked to databases like the public credit registry or the National Health Stack.

Closing Remarks

In his closing remarks, Binoy Viswam (Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha) Appreciating convening the Janta Parliament as a means to actualize ‘people’s democracy’, Mr. Viswam cautioned against the degeneration of the country into a police state where people are under a constant watch. He further lamented how the state, which is expected to come to the rescue of the people in a democracy, looks the other way as personal data is mined for corporate interests. Calling for people to rally around Article 21 of the Constitution, he highlighted the need to evolve dialogue around the new meanings of the right to live with dignity in the 21st century. Bringing into focus the role Parliament and Committees can play in advancing digital rights, he spoke of his experience being a part of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Science & Technology which decided to look into the impact of digital platforms like Whatsapp, Twitter, and Facebook in early 2019 and summoned the representatives of those companies to appear before the Committee.

The session ended with voting on 8 Resolutions all of which were adopted by the House with a majority of participants voting in favour. Article 21 Trust and Rethink Aadhaar had come together to anchor the session on Technology and Surveillance.

This discussion was held as part of the sixth of twelve sessions convened under the Janta Parliament initiative.

We are grateful to Kruttika Susarla for her amazing illustrations!