This is how the Aadhaar-based system works in welfare: To get Aadhaar, a 12-digit number, residents are required to submit biometrics and demographic information to private enrolling agencies hired by the state governments. Biometrics include the scan of all fingerprints, face, and the iris of both eyes. The demographic information includes name, date of birth, gender, residential address.

The information is then sent to the Unique Identity Authority of India's Central Information Data Repository where it is compared against every other person who has previously enrolled. This is called "de-duplication".

When the government requires Aadhaar number in a particular program, the information a resident has provided to the Programme Department (for example, rural development department in case of pensions, or food department in case of rations) along with Aadhaar number is “seeded” or matched with the information that person has provided to UIDAI. After this, every time a resident accesses the welfare program, they are authenticated based on data stored against their Aadhaar number. Under the public distribution system or rations, for instance, a ration beneficiary must place a finger on a “point of sale” machine, which uses the internet to match the individual’s fingerprints against data stored on the centralised Aadhaar database. Once the beneficiary’s identity is confirmed, the ration shop owner hands over the rations at the prescribed rate.

This system requires multiple fragile technologies to work at the same time: the point of sale machine, the biometrics, the Internet connection, remote servers, and often other elements such as the local mobile network. Further, it requires at least some household members to have an Aadhaar number, correctly seeded in the PDS database.

In rural India, especially in the poorest States, even in State capitals, network failures and other glitches routinely disable this sort of technology. Note that Internet dependence is inherent to Aadhaar since there is no question of downloading the biometrics.

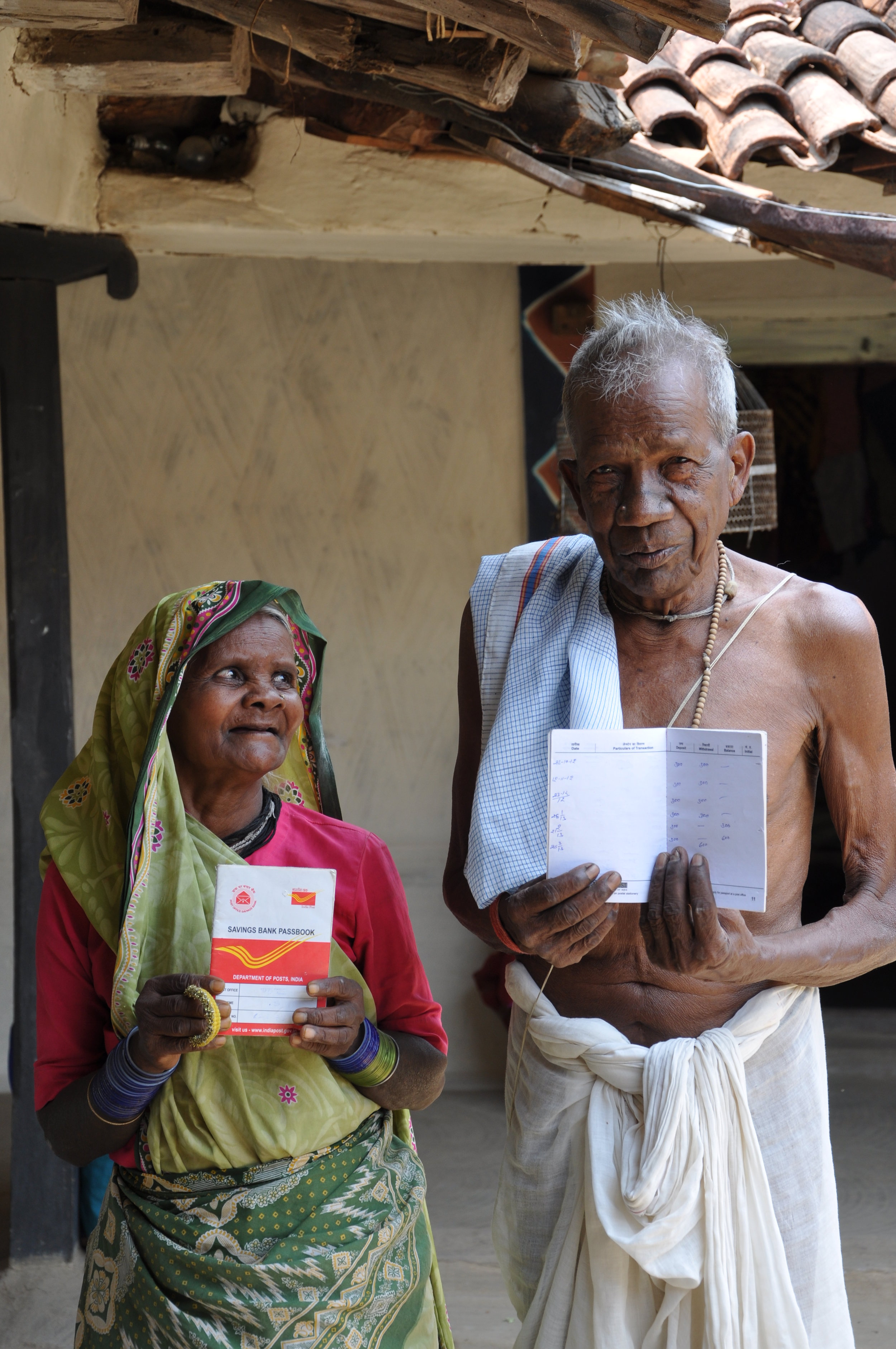

In villages with poor connectivity, the Aadhaar-based system is beginning to exclude thousands of users. Biometrics have consistently failed for people who depend on manual labour for a living as their fingerprints get omitted. In Rajasthan, thousands of elderly were wrongly declared “dead”, and their pension stopped because one or many of these technologies did not work well. Many of them are still trying to get the administration to recognise them as “living”. Thousands others were wrongly excluded and denied rations in the middle of a drought earlier this year. Imposing a technology that does not work on people who depend on it for their survival is a grave injustice.